Trevor Griffiths & a book launch in Basford

In the summer of 1976, just before I started university, I worked for the council, cutting lawns. Summer jobs were scarce in Colne but this was better than the paid work I’d had before: a warehouseman at ASDA and running the conveyor belt for Findel’s, a packing firm in Nelson. I was waiting to see if I got good enough A level results to take me to Nottingham, where I had a place on a Law degree, provided I got at least two Bs. After four weeks, I was made redundant at short notice, but the other student they’d taken on had a dad who worked at the council. He insisted that we had to have a minimum two weeks’ notice, so we were taken back on. For those last two weeks, I swept streets, alone.

A little lesson there about how the world worked. I’d only got the job in the first place because my local councillor had put in a word for me. I had, for a year, belonged to the Young Liberals, and done some leafletting for him. Later, my mum would join the local Liberals and end up becoming deputy council leader and mayor of Pendle, but that’s another story.

I didn’t watch a great deal of TV apart from The Old Grey Whistle Test and Dr Who, but one new late night programme grabbed me from the first episode. It was a series starring Jack Shepherd as a radical left wing MP in a Northern constituency (the fictional Leigh) and his fights within a Labour party that had a right wing leader, a Prime Minister played by Arthur Lowe (Captain Mainwaring from Dad’s Army) and one hard left cabinet minister played by Alan Badel. I rewatched the series on DVD last year and it remains a remarkable piece of drama, one that undoubtedly influenced my decision, in 1980, to join the Labour Party. Three years later I was blown away by Richard Eyre’s TV version of Comedians (which I arrived in Nottingham a year too late to see at our Playhouse, which commissioned it). Two years after that – by which time I was a Labour party activist – I was deeply impressed by his 1981 Play for Today set around the 1945 General Election, Country.

I’m not sure precisely when I conceived the idea of writing my own variation of Bill Brand, about a left leaning Labour MP in the 1990s, but it was probably in the late 80s, when I was getting going as a writer (my first short story appeared in 1989 and first novel a year later). By the mid-90s, when I was making a good living as an author of YA fiction and working out where to go next, it seemed inevitable that New Labour would achieve power at the next election. I visited the House of Commons twice, just before and after the 1997 General Election, being shown around by an old comrade who was now my MP, John Heppell. John kindly offered me a job as an unpaid researcher so that I could soak up the atmosphere of New Labour and get background material. However the then chief whip, Donald Dewar, blackballed me on the grounds that I might leak stories to Private Eye. Dewar did me a favour because, while I had a crack at my novel, to be titled Previous Convictions, I soon realised that you couldn’t write about an era until it was over. I wrote The Pretender, itself a new version of something I’d written in the 80s, instead.

By 2010 though, New Labour was over and the time was right to write the novel, which I was beginning to see as a series, or sequence (or saga, I guess, anything beginning with an ‘s’). Another old friend of mine, Meg Munn, had become an MP in 2001, and she gave me invaluable research help – still does, though she stood down in 2015, just before I started writing Death in the Family. This new novel had a troubled gestation (publishers going bust, bereavements, chairing a UNESCO City of Literature) but is published later this month. And it’s dedicated to Trevor Griffiths.

Griffiths is, I think, our most important UK post war political playwright, and the best, with compassion and humour running through a great body of work that takes on many of the big political movements of the twentieth century. This isn’t the place for a long discussion of his work, especially as I hope to write about him at much more length in the not too distant future. After watching the BBC’s repeat of 1981’s Country (part of their Play for Today anniversary celebrations), I wrote Trevor an email (having sourced his contact details from a mutual friend) to tell him how much his work had meant to me and how much I still admired it. This led to a phone call and an invitation to visit and interview him, which I did last summer.

We spent much of a fine summer afternoon in Boston Spa talking about Trevor’s early life, and his career as a teacher. Indeed, there were still former students who, sixty years on, had stayed in touch with him. He showed me some artwork by one of them. The ongoing pandemic has, so far, forced us to postpone the second half of the interview, which I hope to do later this year. Trevor had, I’ve come to realise, through his plays and his telling of some of the most pivotal events of the last century through the eyes of the revolutionary protagonist, taught me a great deal. Hence the second part of the new novel’s dedication. For Trevor Griffiths: comrade, teacher.

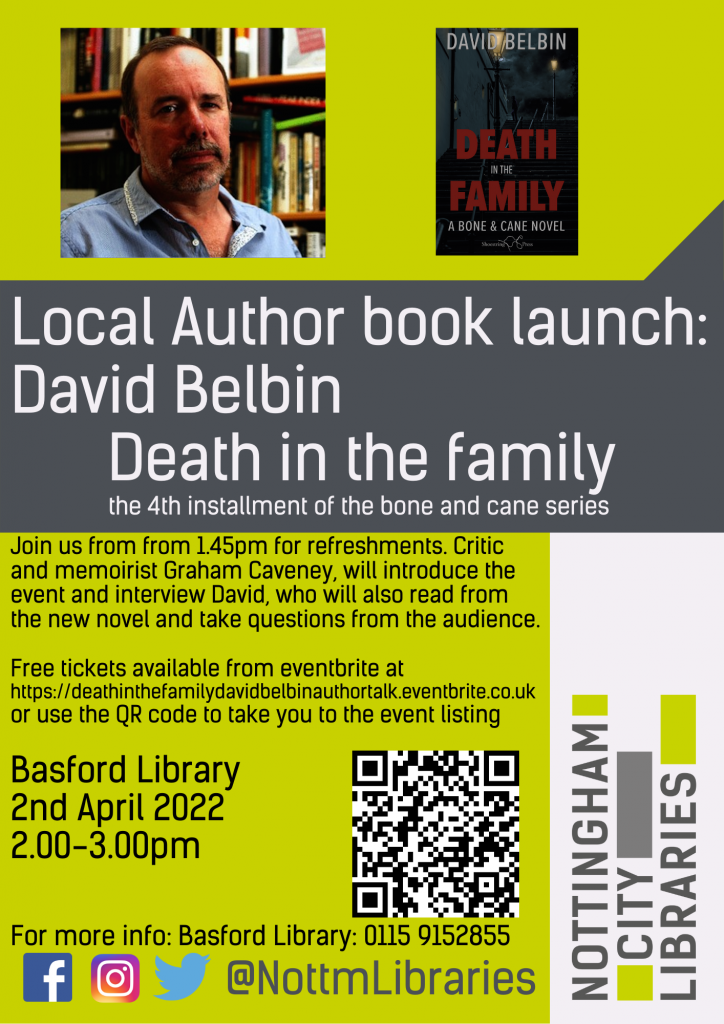

Death in the Family is published by Shoestring Press and will be launched at Basford Library on Saturday, April 2nd at 2pm (doors and refreshments from 1.45). Critic and memoirist Graham Caveney (The Boy with the Perpetual Nervousness) whose On Agoraphobia is published on April 28th, will introduce the event and interview me. I’ll also read from the new novel, take questions and sign books. Full details and booking link here (booking not required but useful to us and acts as a reminder). Thanks to Nottingham City Libraries for hosting. Basford Library is threatened with closure due to government cuts and we want to get as many people as possible into this beautiful library, on the edge of a park, and put pressure on the council to find a way to save it.