Self Censorship & Charles Willeford’s Grimhaven

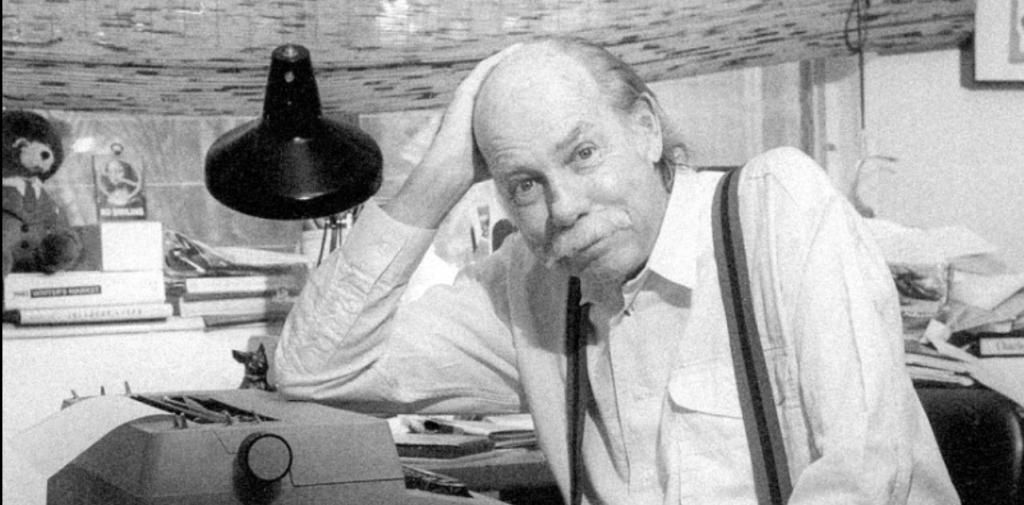

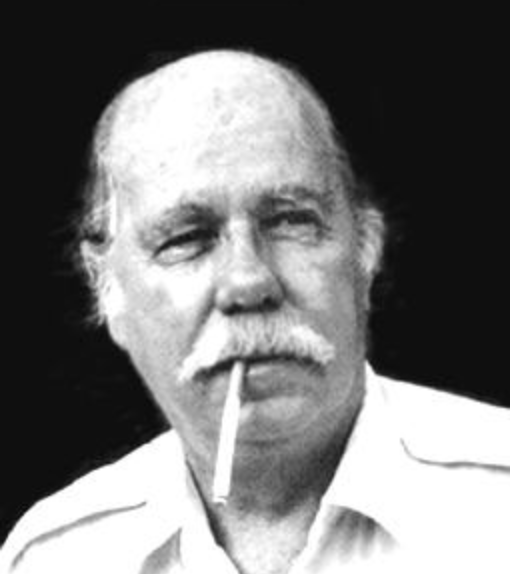

Back in the 80s, I read Charles Willeford’s Hoke Mosley novels as they came out in the UK. They’re bleak but brilliant crime novels written in a stark style – the nearest European equivalent might be Jean-Patrick Manchette. Back in the 80s, they felt like they belonged with the American literary writers known as ‘dirty-realists’, my favourites of whom were Raymond Carver, Richard Ford and Jayne-Anne Phillips. Willeford was older and had been around longer. He could be controversial, as in the novel ‘Cockfighter’, but I hadn’t heard of his most controversial book, the original second Hoke Mosley novel, ‘Grimhaven.’

That remained the case until a week ago, when a post on Bluesky informed me of a place where I could read this book, which existed in a single, typed copy in a university archive someone had photographed and put on the net. The book, I gathered, had been rejected because it was ‘too bleak’. I can handle a bit of bleakness, I thought, and – avoiding spoilers – I tracked down an ePub copy which turned out to be perfectly formatted and proof-read (a rarity in bootleg books) and took it on holiday with me.

Willeford died in 1989, the year before Alex Baldwin appeared in a decent adaptation of the first Hoke novel, Miami Blues (original title – Kiss Your Ass Good-Bye), but his widow, Betsy, is still alive and evidently unhappy that copies of Grimhaven circulate. I can understand why. To explain further requires an enormous spoiler, so if you’re determined to track the book down I suggest you do so before reading on – otherwise, by the time you get to the end of this piece, you almost certainly won’t want to.

Miami Blues concludes with Hoke having left the police force. He has killed an evil man – giving him a second bullet, just to be sure, and was disturbed to find that he enjoyed the experience. Now he lives a simple life, working in a hardware store owned by his father (who has a new wife younger than Hoke) living in a one room apartment also owned by his father, who is about to go on a long cruise. Then, out of the blue, Hoke’s two daughters show up to live with him. They are fourteen and sixteen and he hasn’t seen them for ten years. He stopped paying maintenance to his ex-wife when he quit the force. She is now living with a black baseball star and the girls are in the way, so she’s sent them over to him.

What we get from then on is Hoke having to deal with these two girls, who are happy to see him, want to love him, and deal with the incredibly straitened circumstances they find themselves in with more grace and dignity than their lacklustre father might expect. There’s a lot on how Hoke gets then organised, at times being shockingly racist and disconcertingly frank with the girls (about sex and how to withhold it). It looks like he might have to take a job as a Florida police lieutenant in order to fund his new situation. His father sets him up with the police, who would be glad to have him (he’s a star detective, after all) and also offers him the use of his large house and pool while he’s gone for three months. Depressive Hoke doesn’t want the girls getting used to the luxury, but gives no hint of what he’s going to do next.

The book is nearly two thirds through. It isn’t a crime novel so far (Willeford never wrote a straight forward crime novel in his whole career) but it’s absorbing, very tightly written with compelling characters. You aren’t meant to like Hoke – he’s a bleak son of a bitch, though you can empathise with him – but the girls are sympathetic and you want to know how they’re going to turn out. Also, it’s a fast read so I take it to bed with me, half thinking I’ll finish it that night. And then, out of nowhere, Hoke murders both of his daughters.

It’s hard to convey how shocking this is. As soon as I’d read the passage, I stopped reading. I knew I’d find it hard to sleep and forced myself to pick up Geoff Dyer’s memoir Homework and throw myself back into the 60s until I was too tired to go any further. But I still slept badly, with odd dreams, and finished the book on my plane journey the next day. The detailed description of how he kills the girls and what he does with their bodies are a very difficult read. At no point does Hoke’s point of view address why he did what he did. It’s only at the end, where he’s waiting to get arrested, that his motives are made a little clearer. He knows that he’ll get the electric chair but, with appeals and the amount of time people spend on average on death row, he should have ten years in which he can do a lot of reading and he thinks his life in prison will be a lot more pleasant than the one he would otherwise have had if he was his girls, who would be giving him trouble. This is convincing, up to a point, the point up to which you think why did I never spot that this guy is a complete psychopath? In his only extant audio interview Willeford says that he was told in a writing class that you couldn’t make the reader sympathise with a crazy character and he wanted to prove the teacher wrong. But never trust what writers say, trust what they write. Hoke’s detailed planning of his daughters’ deaths (and, later, retaining a lawyer for his inevitable arrest) suggest the killings are hardly dissociative behaviour. They’re a quasi-rational choice.

Willeford’s agent refused to send Grimhaven out to publishers. Willeford had just resumed his career after many years (some of his earlier books found their way back into print and were even filmed. Mick Jagger starred in The Burnt Orange Heresy as recently as 2019). Willeford might have a high reputation for existential noir. Nevertheless a book this bleak would end any career. Willeford hadn’t written a series before. This sequel would have made it impossible for Miami Blues to become a series. Probably Willeford wrote the novel the way he did in order to avoid writing a series – but then real writers never entirely know why they’ve written something until it’s done. You write the book in order to find out what you think, in my experience. According to Marshall Jon Fisher Willeford later changed his mind and enjoyed writing the three subsequent Hoke novels. (In the radio interview, he claims to have planned the sequel to Miami Blueswith enthusiasm.) He reused some Grimhaven details in those later Hoke novels – including the daughters and how Hoke reduces his wardrobe to two yellow jumpsuits (one washed, then drying while he wore the other).

Is Grimhaven a dark, nihilistic masterpiece? No. There’s plenty of bleakness and dark humour in all the Willeford novels I’ve read (there are several early ones I’ve yet to try), but here’s the thing that prevents it from being a great novel. I don’t believe Hoke’s behaviour in the last third. If Willeford’s testing the reader – how far can I go and keep you with me? – the test falls at the first hurdle.

A sidenote: I can relate to writers wanting to test the boundaries. I used to write Young Adult fiction – writing what were essentially short, adult content crime novels aimed at older teens but published – back in the 90s – within a children’s fiction sphere where self-censorship was rife. If you got past your internal self-censor and a nervous publisher you could be sure that there would be another set of gatekeepers in schools that dared put you on the library shelves. But I was on a roll (up to five 45,000 words books in a year) and couldn’t stop myself from writing whatever the hell I felt like writing. In my eleven The Beat police novels I tended to do one for them and one for me – a straight mystery then a more topical issue. The publishers went along with it because I was, for a few years at least, the best-selling writer they had. They did put a warning about upsetting content on the fourth Beat novel, Asking For It (about rape and sexual assault) which halved the sales, and later delayed the standalone about a teacher/pupil sexual affair Love Lessons by two years (it became, nevertheless, my best seller in the UK, but that’s another story). My final YA novel Denial was nearly never published because of its shocking twist. I was forced to rewrite the ending in a way I soon regretted and have chosen never to republish it as an eBook.

“His humor was often gruesome,” Willeford’s widow Betsy said in a 2009 interview with The Atlantic. But this is not humorous book. There is one sort of humorous passage. I’ve mentioned how the novel ends but, before we get there, something else happens. Hoke, having moved the girls’ bodies to his father’s house (with gruesome details that I’ll spare you) drives to LA planning to kill his wife’s new boyfriend. He buys a shotgun. Then he decides to go to the movies. And he goes to see one of my favourite films of all time, Bill Forsyth’s Local Hero (my partner, Sue, loved this film so much that she chose it as the last film we watched together, for the umpteenth time, ten days before her death). Here’s the section.

“The movie, Local Hero, had little or no plot and took place in Houston and in a small

Scottish fishing village. It featured Burt Lancaster as a crazy financier and a young actress with webbed toes. There was no explanation given for her webbed feet, but because she spent most of the time in the water, and because there was talk about mermaids, Hoke guessed that the audience was supposed to believe that the girl was, indeed, a mermaid. The small bay in Scotland, washed by the warm waters of the Gulf Stream, looked like a nice place to swim. But the story ended unhappily. An old man, who lived in a driftwood cottage on the beach, was forced out of his home by the Texas oil company.”

This sour take on the movie, which misreads the ending (which I won’t spoil – LH is a warm, wonderful masterpiece) suggesting that Hoke isn’t paying attention, might tell us something about Willeford or it might tell us something about how he wants the reader to understand Hoke’s pessimism. However, given that the majority of Willeford’s readers won’t know anything about the film beyond what they read in the novel (and, as every novelist knows, novel have to be self contained,) the latter seems unlikely.

What comes next is a surprise.

“After the movie, Hoke returned to the A-OK park-and-lock lot and discovered that someone had stolen his truck.” The gun was in the truck, so Hoke is in no position to shoot Curly, his wife’s new partner. Instead he improvises an attack on the football player with a letter opener and succeeds only in making him bleed, an absurdly comic scene. He does not tell Curly or his ex-wife that he’s killed the girls.

The writer Ray Banks (who I worked with on two terrific novelettes when I edited Five Leaves’ Crime Express series) is the only other person I know who’s read Grimhaven. He reread Willeford during the pandemic (should you read this, Ray, I did try to get in touch to discuss the book with you). He calls Grimhaven ‘a dark, vicious, beautifully written book, and it’s absolutely indisputable that it would have wrecked Willeford’s career had it been published in the wake of Miami Blues. In foreshadows the breakdown Hoke suffers in Sideswipe, and it underlines the darker, less immediately likeable characteristics that make Hoke such an enduring character to readers like myself.’

Willeford’s last Hoke Mosley novel, The Way We Die Now (its title a nod to the first masterpiece of my favourite crime writer, Ross McDonald, The Way Some People Die) got an advance of $225,000 – the biggest money of his career. Sadly, he didn’t get long to spend it, or live to see the 1990 movie of Miami Blues. Having come back to his work and been reminded of how good it is, I mean to read some of the earlier ones I missed. I pulled out my copy of New Hope for the Dead (the second Hoke novel, which he wrote to replace Grimhaven, whose existence makes the title extra ironic) to see how the two relate. I was going to reread it before I wrote this post. However, the book I wasn’t meant to read has left a bad taste in my mouth. I don’t think I’m ready.

Another autobiographical sidenote: I had an idea for a story once. It was a memorable idea and later, someone else (a much more successful author, no longer with us) published a book using roughly the same idea (pure coincidence – ideas are in the air and all that counts is what you do with them). She just about got away with it, or so the reviews suggested. I was never tempted to read it. The idea could have been used for propaganda for a cause I didn’t support, and – while I’m happy to court controversy, or so it says in many things written about my work – I didn’t want to be a poster boy for… no, not going to go there. Some things are best left unwritten. Because even if you don’t publish them, unless you destroy every trace, chances are the story will get out, and affect its readers. You are responsible for what you write. I won’t be able to forget Grimhaven. Part of me already regrets reading it.

Curly was a baseball player in this series, not a football player.

Corrected, thanks.