Graham Greene in Nottingham and ‘The Pretender’

Nottingham Playhouse’s production of ‘Our Man In Havana’ opens tomorrow and plays Nottingham before touring. Below is an article I wrote about Greene, Nottingham and my novel ‘The Pretender’. The article (along with interesting pieces about Havana and working with Greene) can be found in the programme for the play, which I’m going to see next week.

Nottingham Playhouse’s production of ‘Our Man In Havana’ opens tomorrow and plays Nottingham before touring. Below is an article I wrote about Greene, Nottingham and my novel ‘The Pretender’. The article (along with interesting pieces about Havana and working with Greene) can be found in the programme for the play, which I’m going to see next week.

When Graham Greene arrived in Nottingham, he was an Oxford graduate, just turned 21, who wanted to be a journalist. He hoped that a brief spell as a trainee subeditor on the Nottingham Journal would stand him in good stead for a post in London. On November 1st, 1925, he moved into lodgings on Hamilton Road in Forest Fields. ‘When I read Dickens on Victorian London,’ he wrote in his autobiography, A Sort Of Life, ‘I think of Nottingham in the ‘20s. Trams rattled downhill through the goose-market and on to the blackened castle. Against the rockface leant the oldest pub in England with all the grades of a social guide: the private bar, the saloon, the ladies’, the snug, the public… I had found a town as haunting as Berkhamstead, (one) where years later I would lay the scene of a novel and of a play.’

Green visited many of the town’s cinemas, where matinee seats in the stalls cost fourpence. He loathed his boarding house, though he mined it for material. After two weeks, he moved from Hamilton Road to Ivy House, Ivy House, near the Arboretum, later fictionalised as ‘two rows of small neo-Gothic houses lined up as carefully as a company on parade.’ Ivy House was probably on what is now All Saints Road and accessed from a road which was then nameless but known as ‘All Saints Terrace’ and is now officially Goodwin Street (see the photos two posts below). It has been claimed as the model for disreputable houses in several of Greene’s novels.

Greene was very taken by the city’s fogs, writing to his fiancée Vivien:

‘There’s a most marvellous fog here today, my love. It makes walking a thrilling adventure. I’ve never been in such a fog before in my life. If I stretch out my walking stick in front of me, the ferrule is half lost in obscurity. Coming back, I twice lost my way, & ran into a cyclist, to our mutual surprise. Stepping off a pavement to cross to the other side becomes a wild and fantastic adventure… if you never hear from me again, you will know that I am moving round in little plaintive circles, looking for a pavement.’

The only writer Greene met in Nottingham was Cecil Roberts, now best known for the room named after him in the City library but, in his day, a prolific and popular novelist. Roberts invited Greene to tea. They talked for an hour, after which Greene wrote ‘an educated person in Nottingham is as precious & rare a find as jam in a wartime doughnut!’

In order to marry Vivien, it was necessary for Greene to convert to Roman Catholicism, which later became so important in his fiction. He took instruction in the Catholic Cathedral opposite Nottingham Playhouse. His tutor was Father Trollope, once a West End actor and himself a late convert.

Greene only stayed in Nottingham for four months, a period he shortens by a month in his autobiography. He left without a job to go to, and wrote to Vivien from London: ‘Thank God, Nottingham is over. It’s like coming back into real life again, being here.’ Ten days later, he got a job on The Times, a job he wouldn’t have got without his experience on the Nottingham Journal.

Greene set one of his best early novels, A Gun For Sale in Nottingham, lightly fictionalised as Nottwich, as well as his play The Potting Shed. Although he later talked about the city affectionately, the author was not so kind while he was here. ‘This town makes one want a mental and physical bath every quarter of an hour,’ he wrote. ‘There’s absolutely nothing worth doing in this place. No excitement, no interest, nothing worth a halfpenny curse.’ Yet the city was important – some argue, crucially important – to his fiction, presenting him with a first hand experience of the working class that may have prevented him from becoming yet another chronicler of upper middle class life in London.

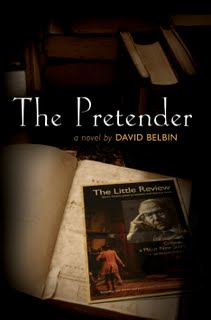

As a student arriving in Nottingham as a student in the late 70’s, I had no idea of Greene’s connection with the city. I discovered his novels in the university library and devoured all of them in the space of a month. Later, I worked my way through his short stories while revising for my finals. I’ve have remained an admirer ever since. Inevitably, there had to be a Greene story about Nottwich in my novel about literary forgery, The Pretender.

The book’s about Mark, a precociously talented young man who develops a lucrative capacity for literary forgery. A Hemingway pastiche he’s written is taken for the real thing and sells for a fortune. To help save the literary magazine he works for, Mark decides to forge a ‘lost’ Greene story. I had the idea for this novel when I was in my 20’s and Greene was still alive. I considered writing to the author, asking for his blessing and perhaps a page of ‘real’ Greene to pass off as a forgery (I wouldn’t dare include an actual imitation). Then, I wasn’t audacious enough to approach Greene, though now, of course, I wish I had. I like to think the idea would have amused him.

More recently, when I came to write the published version of the novel, I chose to set it in 1991, the year that Greene died. The faked Greene story at the heart of the novel has a Nottingham connection. It was supposedly written in what I think of as Greene’s peak period, the 1950’s, and mentions Our Man In Havana because Greene’s 1958 novel has a reference to the fictional Nottwich and because it is my favourite of the novels that Greene described as ‘entertainments’. On my first visit to Cuba, I visited many of the novel’s settings, which are easy to track down in present day Havana.

In The Pretender, Greene gets to see Mark’s faked story just before his death. Unsurprisingly, he cannot remember writing it. But prolific authors cannot be expected to remember everything they produce, particularly when, as Greene did during that period, they use chemical stimulants to increase their productivity. Greene expresses his doubts privately, but is happy to let the forgery be published. One of the best things about Greene, as playgoers new to Our Man In Havana will discover, is his wicked sense of humour.

One Reply to “Graham Greene in Nottingham and ‘The Pretender’”